Python 101 - Introspection

One of the reasons Python is special is that it provides lots of tools that allow you to learn about Python itself. When you learn about yourself, it is called introspection. There is a similar type of introspection that can happen with programming languages.

Python provides several built-in functions that you can use to learn about the code that you are working with.

In this chapter, you will learn how to use:

The

type()functionThe

dir()functionThe

help()functionOther useful built-in tools

Let’s get started!

Using the type() Function

When you are working with unfamiliar code, it can be useful to check and see what type it is. Is the code a string, an integer or some kind of object? This is especially true when you are working with code that you have never used before, be it a new module, package, or business application.

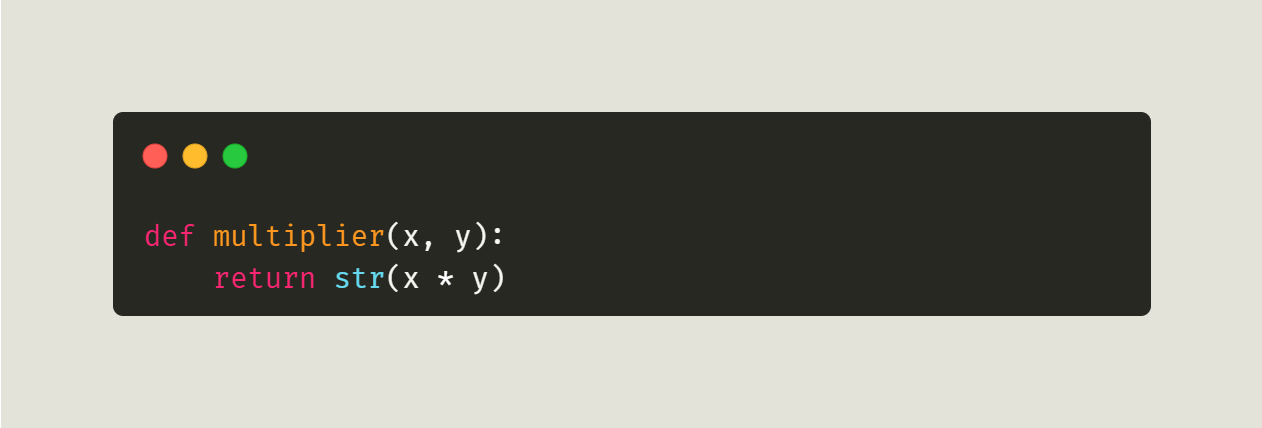

Let’s look at an example:

You will encounter lots of code with no documentation or incorrect documentation. This is an example of a function that appears to multiply numbers. It does, in fact, do that, but notice that instead of returning a numeric value, it returns a string.

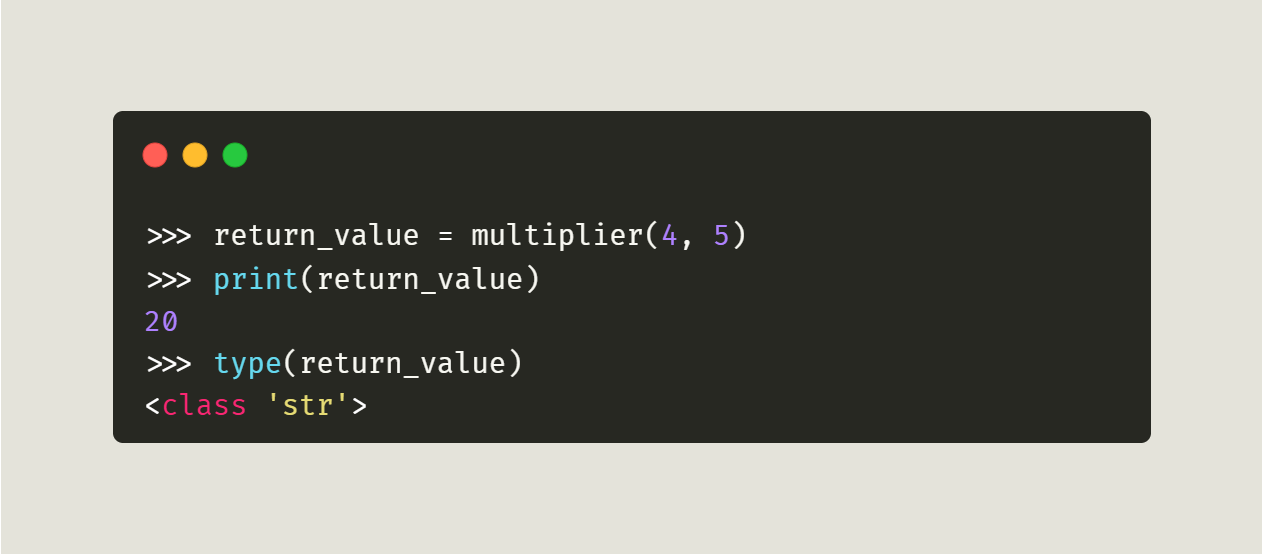

This is where using the type() function can be valuable. Let’s try calling this code and checking the return type:

Looking at the code, you would expect a function named multiplier() to take some numeric types and also return a numeric result, and when you print out the result, it looks numeric -- however, it is a string! You will actually run into this issue quite often and it can lead to some weird errors.

Using the dir() Function

There are thousands of Python packages that you can install to get new features in Python. You will learn how to do that in chapter 20. However the Python standard library has lots of built-in modules that you may not be familiar with either.

You can use Python’s built-in dir() function to learn more about a module that you are unfamiliar with.

When you run dir(), it will return a list of all the functions and attributes that are available to you.

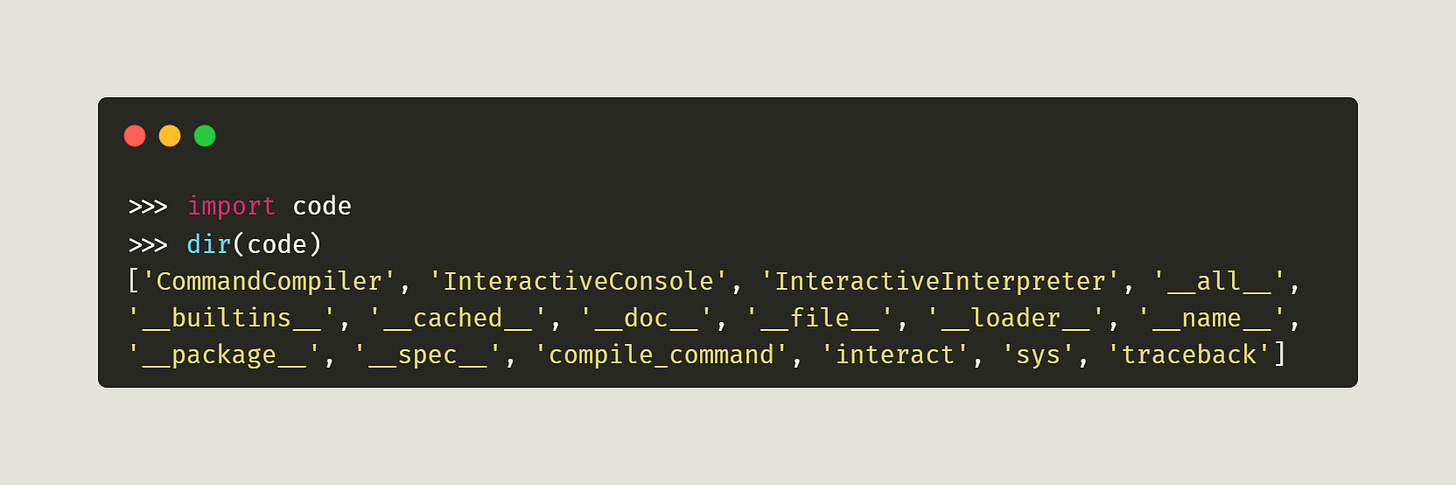

Let’s try using it on the code module:

Most people aren’t familiar with the code module. You use it to create read-eval-print loops in Python. One way to learn how you might use this mysterious module is to use the dir() function. Sometimes by reading the module’s function names, you can deduce what it does. In this example, you can see that there is a way to compile_command and interact.

Those are clues to what the library does. But since you still aren’t sure what they do, you can always ask for help().

Getting help()

Python also provides a useful help() function. The help() function will read the docstrings in the module and print them out. So if the developer added good documentation to their code, then you can use Python to introspect it.

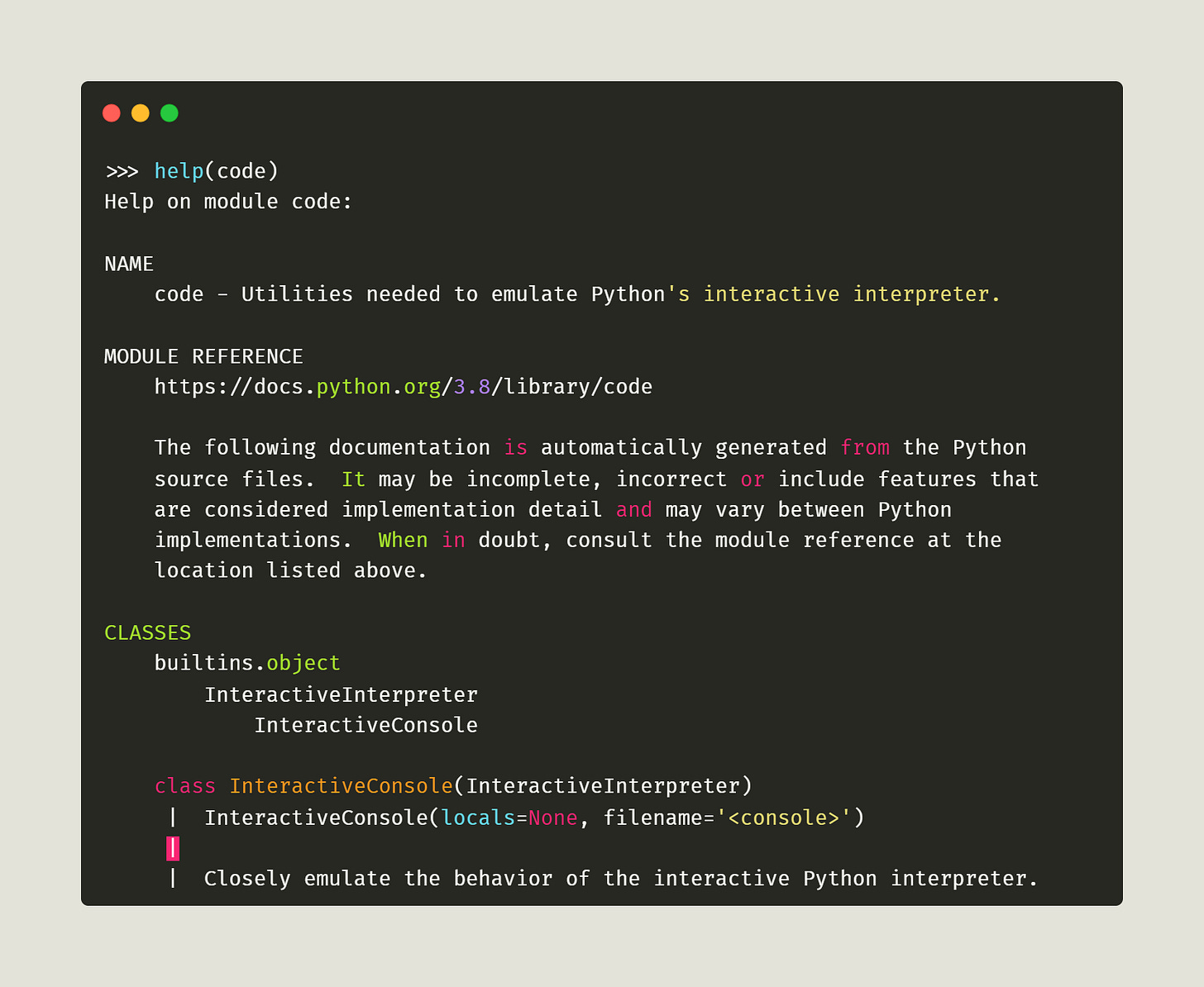

Let’s give it a try using the code module:

This example shows the first page of help that you get when you run help(code). You can spacebar to page through the documentation or return to advance a line at a time. To exit help, press q.

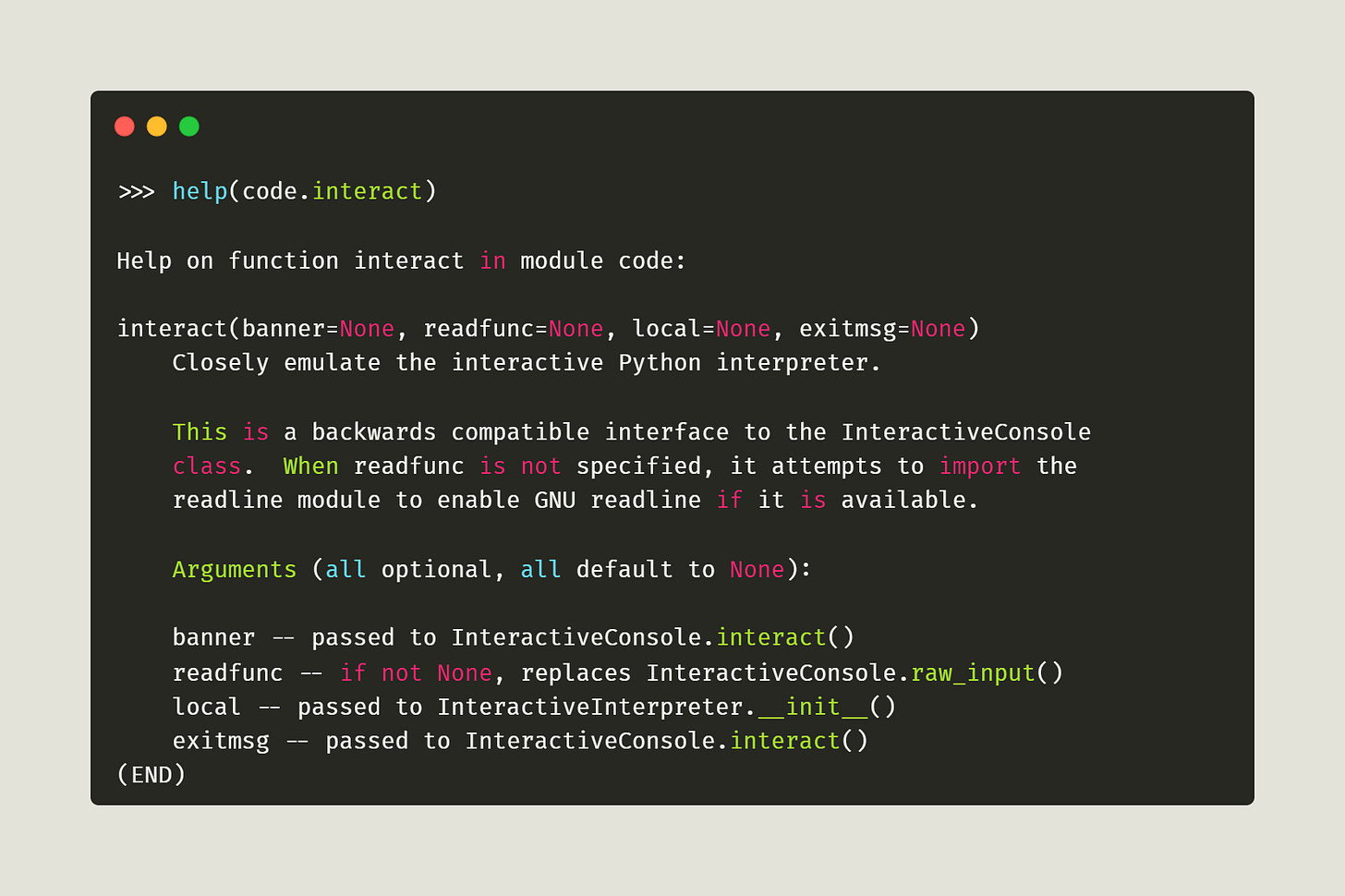

Let’s try getting help on the interact() function:

You can use dir() to get information on the methods and attributes in an unfamiliar module. Then you can use help() to get more details about the module or any of its components.

Other Built-in Introspection Tools

Python includes several other tools you can use to help you figure out the code.

Here are a few more helpful built-in functions:

callable()len()locals()globals()

Let’s go over these and see how you might use them!

Using callable()

The callable() function is used to test if an object is callable. What does that mean though?

A callable is something in Python that you can call to get a result from, such as a function or class. When you are dealing with an unknown module, you can’t always tell what’s a variable or a function or a class. The help() function from before will tell you, but if you don’t want to go into help mode, using callable() might be the way to go.

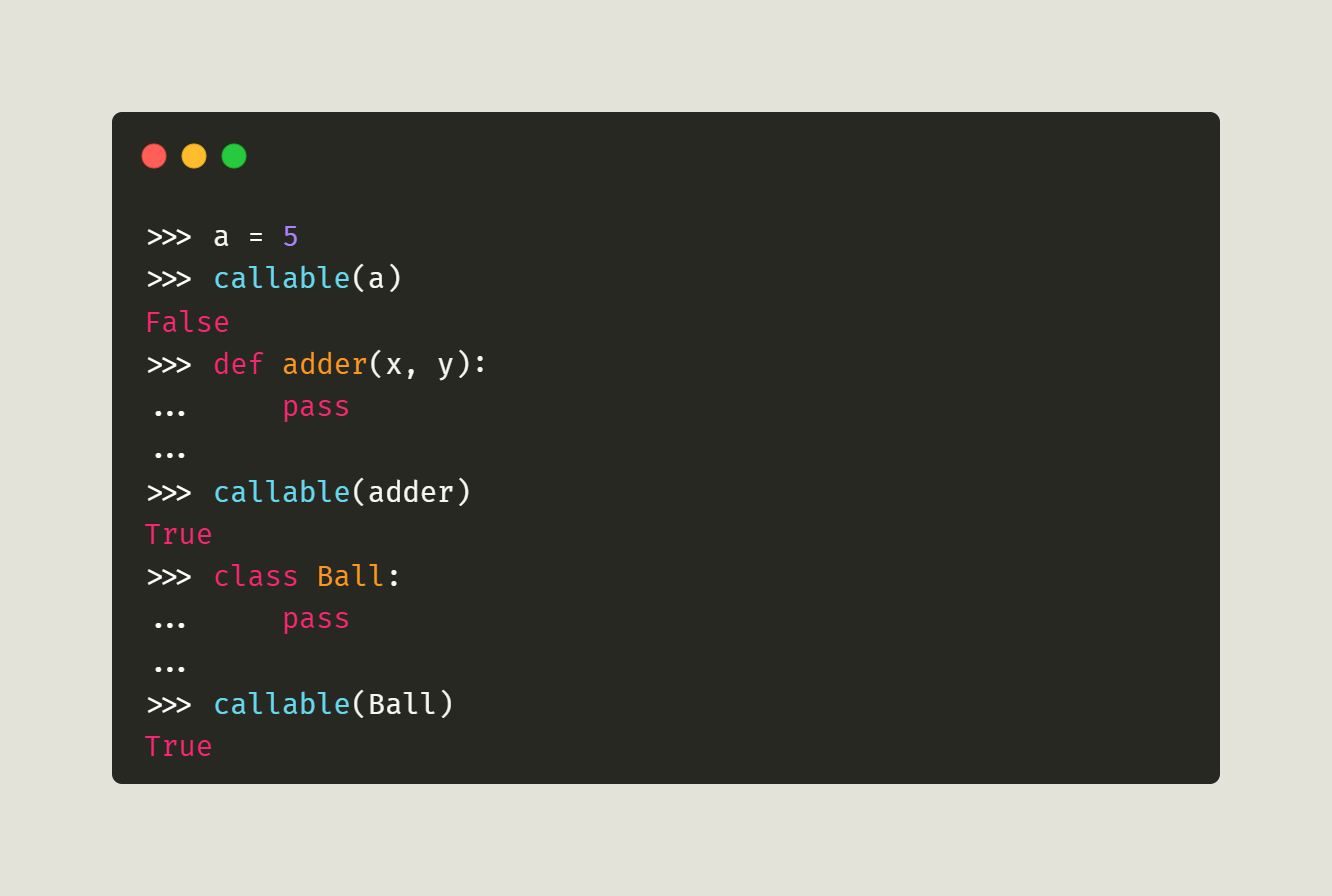

Here are some examples:

The first example shows that a variable is not a callable object. So you can say with good confidence that the variable, a, is quite probably a variable. The next two examples are testing a function, adder, and a class, Ball, with callable(). Both of these return True because they can both be called. Of course, when you “call” a class, you are instantiating it, so it’s not quite the same as a function.

Using len()

The len() function is useful for finding the length of an object. You will probably end up using it a lot for debugging whether or not a string or list is as long as it ought to be.

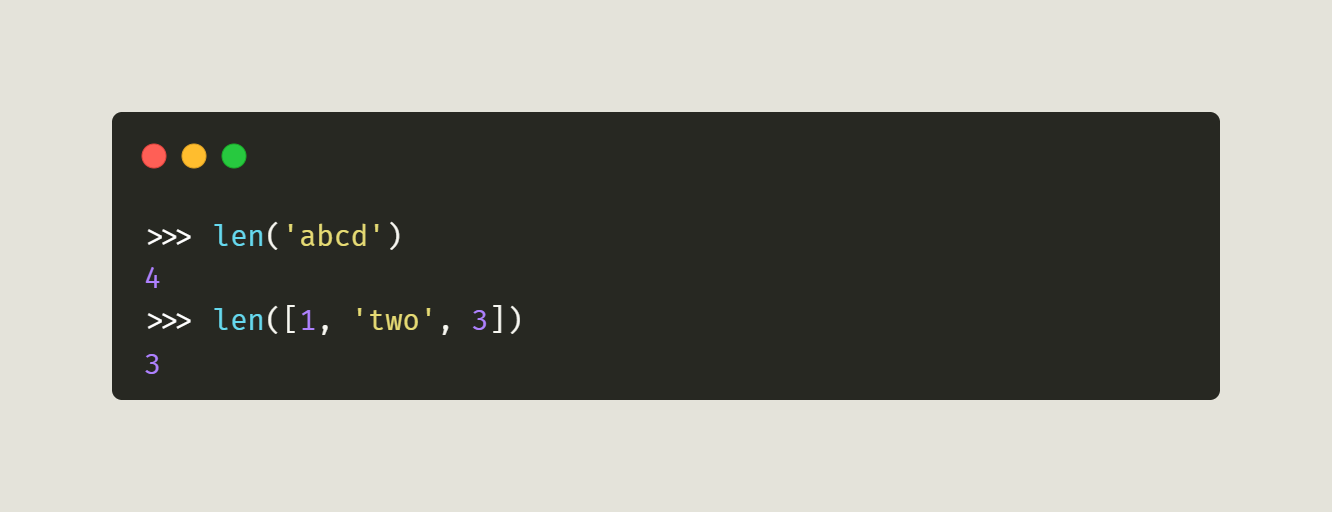

Here are a couple of examples:

You can use len() on many different types of objects in Python.

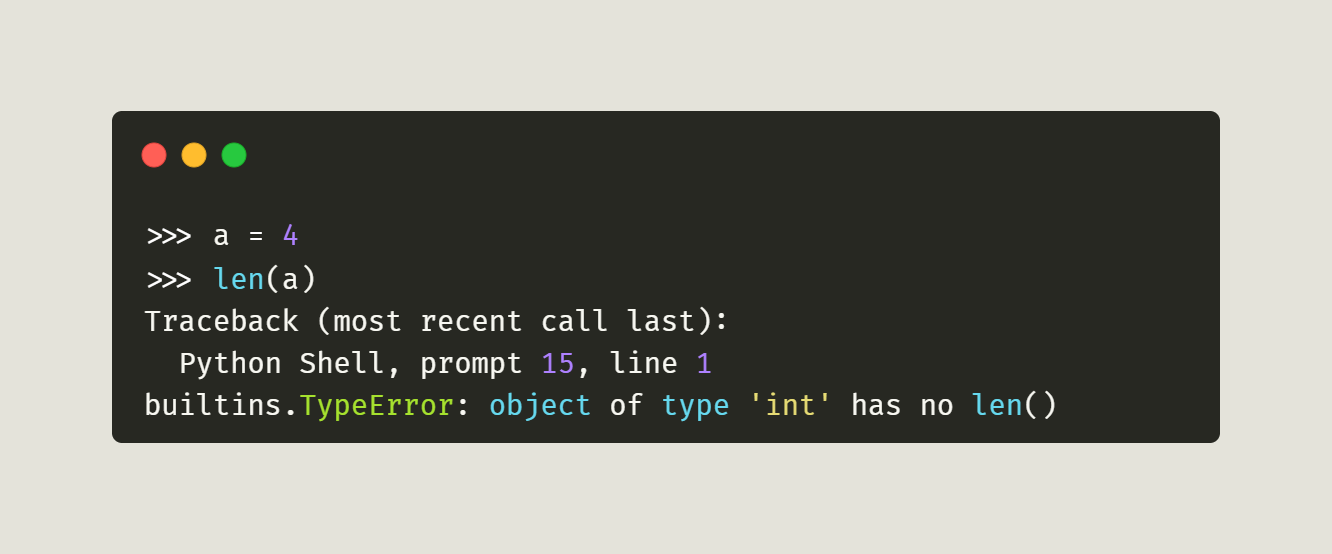

However, there are times when it won’t work, such as with integers:

Using locals()

The locals() function returns a dictionary of the current local symbol table. What that means is that it tells you what is currently available to you in your current context, or scope.

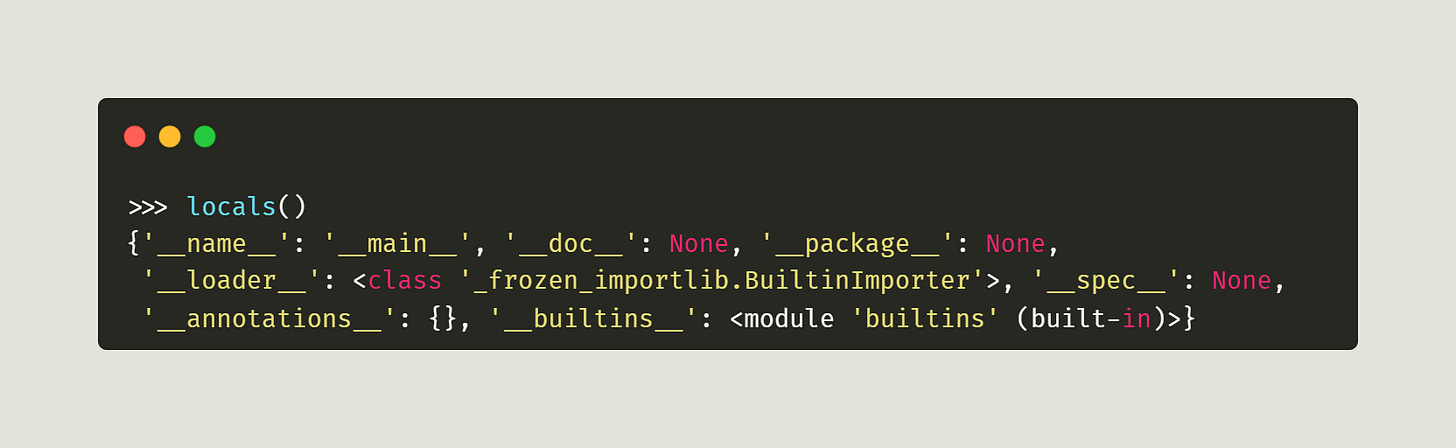

Let’s look at an example. Open up the Python REPL by running python3 in your terminal. Then run the following:

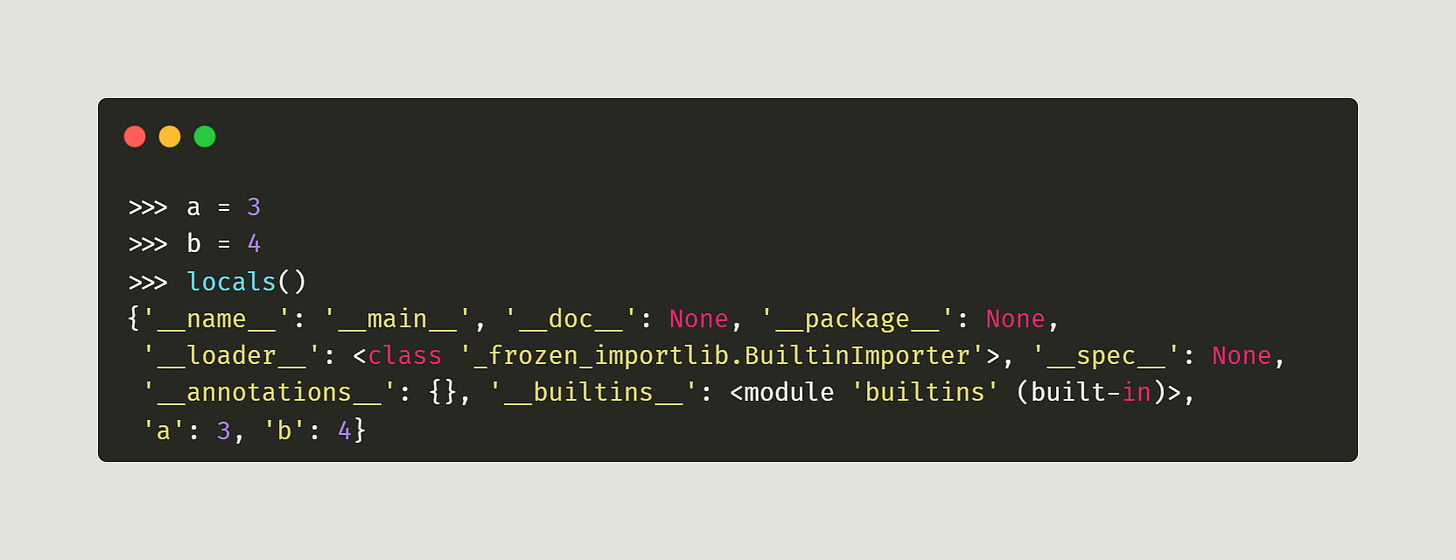

This tells you what is currently in your namespace, or scope. These aren't especially useful, though. Let's create a couple of variables and re-run the command:

Now you can see that the variables you created are included in the dictionary.

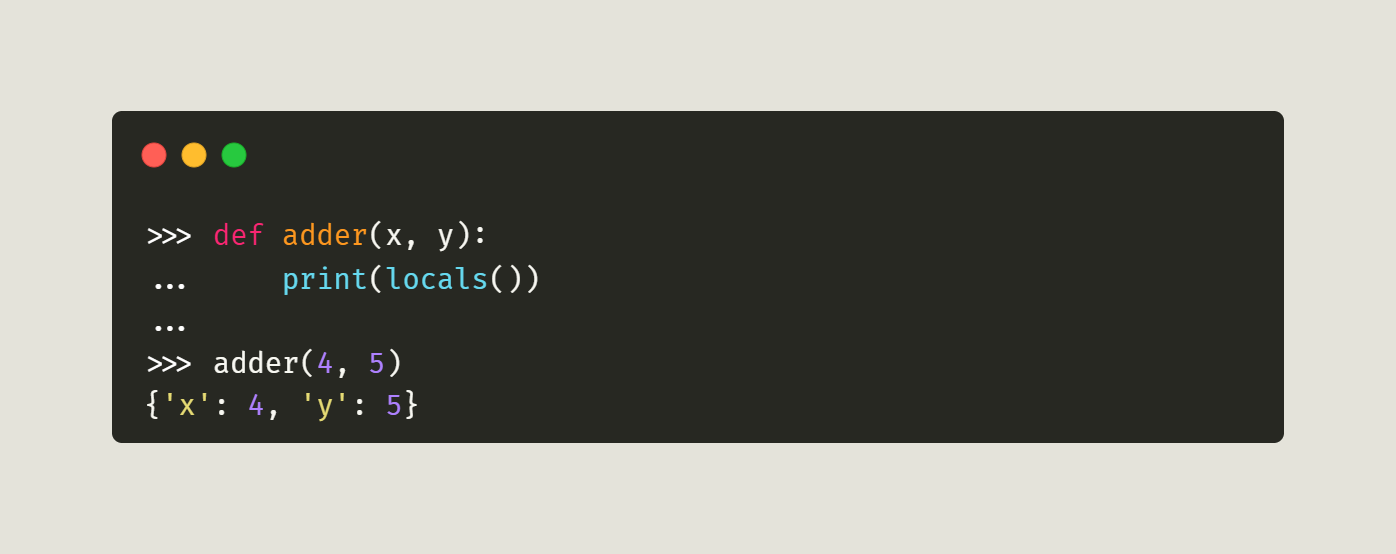

Using locals() becomes more useful when you use it inside a function:

This let’s you see what arguments were passed into a function as well as what their values were.

Using globals()

The globals() function is quite similar to the locals() function; the difference is that globals() always returns the module-level namespace, while locals() returns the current namespace. In fact, if you run them both at the module level (i.e., outside of any function or class), the dictionaries that they return will match.

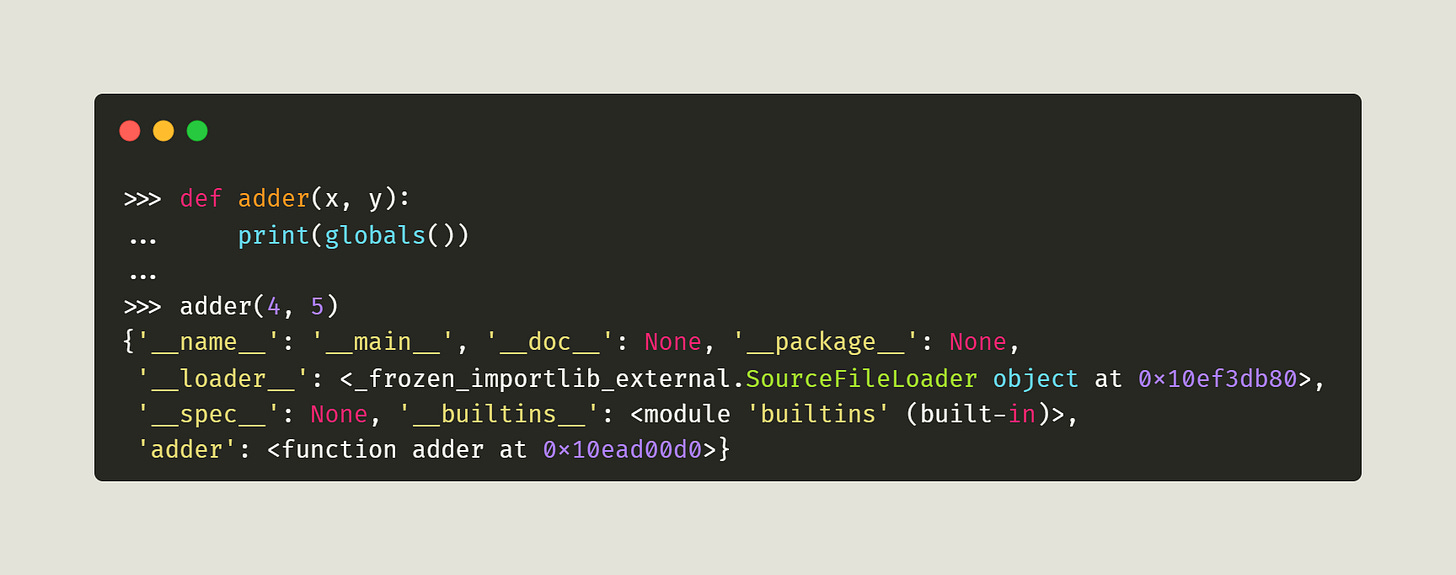

Let’s try calling globals() inside of adder():

As you can see, when you run this code you get the module level attributes, functions, etc., included in the dictionary, but you do not get the arguments to the function, nor their values.

Wrapping Up

Python has a rich set of tools that you can use to learn about your code and other people’s code. In this chapter, you learned about the following topics:

The

type()functionThe

dir()functionsThe

help()functionOther useful built-in tools

You can use these tools together to figure out how to use most Python packages. There will be a few that are not well documented, both on their website and internally too. Those kinds of packages should be avoided as you may not be able to ascertain what they are doing.

Really solid breakdown of introspection tools. The locals() returning a dictionary of the symbol table is one of those features that seems mundane until you're debugging complex nested functions and realize how powerfull it is. I recently ran into a situation where I needed to dynamicaly inspect function arguments and seeing them laid out in dictionary form made the whole prcoess way cleaner than trying to parse them manually.